Breast ironing

Joe Penney

Joe Penney

Julie Ndjessa, pictured here on the left, was just 16 when her mother took a hot stone and pressed it to her chest.

Painful as it is, this practice of “breast ironing” is not uncommon in Cameroon, where mothers sometimes flatten their daughters’ breasts in the belief that it will make them less attractive to men, protecting them from early pregnancy. The custom can cause long-term health problems, and Ndjessa now campaigns against it.

Ndjessa runs weekly sexual education sessions for young women like those pictured above, during which she raises awareness of the risks of breast ironing.

New government research shows that the practice has declined by 50 percent since it was first accidentally uncovered during a 2005 study by the German Technical Cooperation Agency (GTZ).

A successful nationwide awareness campaign in schools, churches and across media outlets has helped to draw attention to the harmful physical and psychological consequences. Nevertheless, the practice still occurs and is thought to affect around 1.3 million girls today.

Priscille Dissake (left) ironed the breasts of her daughter Mick-Sophie Anne (right) when she was just 10 years old.

"Mick-Sophie started developing breasts very early and she was becoming attractive. I wanted to guard her childhood and protect her from men," said Dissake.

Her efforts were in vain. By her own account and that of her mother, Mick-Sophie was raped by an uncle at age 13.

Dissake now feels guilty for her decision: “I meant well. I ask for forgiveness for what I thought was wisdom but turned out to be ignorance,” she said.

“Breast ironing hurts more than childbirth," said Mick-Sophie Anne. "I forgive my mother, but I'll never forget it."

Slideshow

A stone and stick used as tools for breast ironing lie on a stool outside Julie Ndjessa's home in Douala.

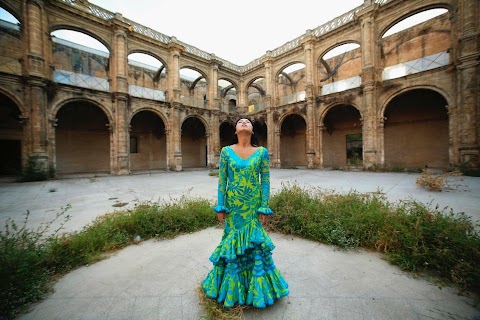

Anne-Simone Ngueti, a 28-year-old survivor of breast ironing, sits in the courtyard of her family home.

Priscille Dissake, who ironed her daughter Mick-Sophie Anne's breasts when she hit puberty at age 10, sits at her kitchen table.

Genevieve Ndjessa stands in front of her house, where her daughter Julie leads weekly educational sessions for young women.

Survivors of breast ironing Mick-Sophie Anne, 31 (left) and Julie Ndjessa, 28, walk through Douala.

Ndjessa, centre, speaks to teenage girls in her family living room.

Girls play a clapping game during the weekly session.

A girl braids her friend's hair after one of the sexual education workshops.

Ndjessa prays with the group of girls after a weekly session.

"Despite the successes that women like Julie have had battling negative practices in their communities, theirs’ is an uphill battle."

Every Friday afternoon, Julie Ndjessa, 28, invites the teenage girls in her neighbourhood in Douala over to her house on a dirt road where she lives with her mother, father and cousin. Giggling, they play clapping games and chat loudly with each other about the week’s escapades. Then Julie gets down to business: educating the young women in her community about the many dangers they face before reaching adulthood.

Over the past few years, one of the main topics she discusses is called “breast-ironing,” a practice used by some mothers in Cameroon to flatten their pubescent daughters’ growing breasts. Done with the intention of protecting young women from early pregnancy by making them less attractive to men, breast ironing is extremely painful and has dangerous long-term health consequences.

There are few people more qualified to speak to young women about this practice than Julie, whose mother Genevieve took a hot stone to her chest when she was 16. She said she harbours no bad feelings toward her mother, who she said did it to try to protect her from the prying eyes of men as she became a woman.

Over the past decade, Julie and other women who have survived the practice have formed an association to fight it through grassroots measures such as workshops and educational sessions throughout the country. Their efforts are supported in part by the German development agency GIZ, with the campaign in Cameroon led by anthropologist and aid worker Dr. Flavien Ndonko. The national campaign has been remarkably successful, dropping the rate of the practice by 50 percent in less than 10 years, according to Cameroonian government surveys.

Julie takes pride in the fact that thanks to the network of human rights workers like herself, young women today are much less likely to go through what she did. But the challenges young women in poverty in Cameroon face are many: rape, early pregnancy, STIs, incest and the everyday problems that come with machismo. There simply aren’t enough resources to address them all.

On the last night I was with her, Julie received some bad news: her cousin, only 16 years old, was pregnant. She felt betrayed, having said to her only two days earlier during the group session that the girls should feel open discussing anything with them.

I left the next morning and she was still in a state of distress. How should she advise her cousin what to do? An abortion would be illegal and risky, and if her conservative Catholic parents found out that Julie had recommended it to her cousin, she would be thrown out of her house. But her cousin was only 16 and the father of the unborn child likely not much older; they would not be able to afford to bring up the child alone, putting financial stress on Julie and her parents’ extremely meager incomes.

Despite the successes that women like Julie have had battling negative practices in their communities, theirs’ is an uphill battle. This was not the first time Julie had had to deal with a crisis like an early pregnancy in the family, and it likely won’t be the last.