Escape to Europe

Marko Djurica

Marko Djurica

With his hands clasped and his head bowed, a migrant sits on the ground after being caught by Serbian border police.

He is one of thousands of people who are apprehended every year while trying illegally to reach Serbia, seen by many as a possible gateway to a better life in Western Europe.

Stark arrows, drawn on a map at a police station in the Serbian town of Presevo, mark out routes used by migrants to cross the border.

In many cases, immigrants travel from Turkey, through Greece to Macedonia and Serbia before they reach Hungary and, with it, the main expanse of the borderless Schengen travel zone that covers much of Western Europe.

A group of migrants who said they were from Syria sit wrapped in a blanket after being apprehended by Serbian border police.

With chaos and conflict raging in the Middle Eastern country, last year saw a huge increase in the number of Syrians trying to enter the Western Balkans in search of asylum in the West.

In Serbia, Syrians made up the single largest group of asylum seekers in the first half of this year.

A Serbian border policeman patrols near the town of Presevo in the south of the country.

Once in Serbia, some of the migrants who are caught and who immediately request asylum are issued preliminary paperwork, dropped off at the nearest bus or train station and given 72 hours to reach one of the country's asylum centres. Many simply try their luck at Serbia's borders with EU members Hungary and Croatia.

Slideshow

A Serbian border policeman looks at a thermal camera screen while on patrol.

An officer patrols near the town of Presevo.

A Serbian border policeman scans the landscape.

Migrants from Syria are illuminated by bright light after being apprehended by the Serbian border police, having illegally entered the country from Macedonia.

A Syrian man sits on the ground after being caught.

Migrants, most of whom said they were from Syria, huddle together after being apprehended.

A girl from the group is held as she sleeps.

A migrant, who said he was from Somalia, is escorted by a Serbian border policeman after being caught entering the country illegally from Macedonia.

A group of migrants are escorted by a border policeman.

Migrants climb inside a police vehicle.

A police van carrying migrants drives away.

A group of migrants sits inside a police station.

An Afghan man has his photograph taken inside a police station after illegally entering Serbia from Macedonia.

A migrant has his fingerprints taken inside a police station.

An asylum seeker looks out of a window at the asylum centre in the village of Bogovadja, some 70 km (43 miles) from Serbia's capital Belgrade.

An asylum seeker sits on a staircase in the centre.

Drawings of national flags decorate a wall at the centre.

"When I decided to follow this story, I had no idea how strong an impact it would leave on me."

I had been thinking how cold it was for this time of year to need both my hoodie and my jacket. A cold, strong wind blew over the hills of no-man’s land separating Serbia from Macedonia. I stood quietly in total darkness for an hour or so until the border patrol officer, looking through his thermal camera, said: “Here they are, I think there must be 40 of them!”

Every year, the Serbian border police catch more than 10,000 (last year 14,000) migrants from Africa, the Middle East, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, who are trying to reach Serbia illegally. They come from Turkey, through Greece to Macedonia and Serbia before they reach Hungary and with it, the borderless Schengen travel zone.

When I decided to follow this story, I had no idea how strong an impact it would leave on me.

Sasha, a policeman, gave me his thermal binoculars and said: “Look to the left, they are ascending uphill, you can see them beautifully, them climbing in a column one by one.”

I spent a full two minutes looking at total blackness until I could make out the tiny white outlines of people hurrying through the forest. It brought back memories of looking at black-and-white film through a magnifying glass.

“Now slowly behind us, we need to be quiet.”

“I’m following you,” I told Sasha, and asked how it would be possible for three policemen in the dark, wide, open hills to catch 40 people. We hid behind a bush along their route and waited. Sasha stayed with me in front while the other two positioned themselves to surround the group.

“When you hear me scream ‘Stop—Police’ then you can start taking pictures.”

The migrants passed a few meters in front of us and I could clearly hear their steps and how quickly they were breathing. In seconds it all played out. Sasha got up, yelled at the group, and I heard the others screaming “police.” Within 20 seconds the group was sitting quietly in a dirt clearing, surrounded by the three cops.

I thought this kind of operation needed more officers and all the trappings of the police. Everything became clearer when the battery-powered lamps and jeep headlights shone on the faces of the people.

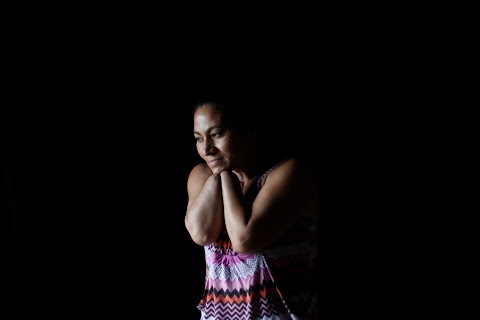

Scared and mostly in their twenties, they looked at us with total uncertainty. A few spoke English, so we began somehow to understand one another. I was taking pictures the whole time but I could not take my eyes off one family, who I quickly found out had travelled all the way from Aleppo, Syria. They looked to me like any family from my neighbourhood. They told me that their house had been destroyed six months ago and that they had nothing left other than a wish to search for a better life.

I was most occupied with six-year-old Fatima and her two brothers, both under 12. One of the boys was shaking from cold. Their father, who had been a high school teacher before the war, tried to pull him close for warmth but he was still freezing. After I took a few photographs, I took off my jacket and offered it to him. The father smiled, looked me in the eyes and said, “merci.”

As we drove to the police station in the town of Presevo, I asked Sasha what would happen to them.

“If they ask for asylum, we will give them papers that will give them 72 hours to go to one of Serbia’s three asylum centers. If not, we will ask the Macedonian border police to take them back because we have clear evidence that they came from Macedonian territory.”

At 3:00 a.m. I headed back to my hotel. The next day I came back and immediately asked about the family.

In the morning, Sasha told me that they asked for asylum and left. “But where to?” I asked. He said he wasn’t sure which of the centres they went to, and that it would be hard to find them.

“Oh! And by the way,” he said, “They left your coat!

“What! They need it a lot more than I do!” I said.

“I know”, Sasha replied, “and I told them that, but the father just repeated ‘merci.’”

They were too proud to accept the gift. I had to find them.

That day, we went on patrol again with the police, this time with the sun high in the sky. Local farmers pointed out a group of immigrants setting off from their fields. The police got another thirteen, mostly from Afghanistan and Somalia. One Somali was fasting for Ramadan despite the arduous trip. Each had stories to tell, but I couldn’t get the Syrian family off my mind.

I called the centre for refugees and asylum with the little information I had about the family, and waited for a response. If they go to any of the centers, I will surely find them, I thought. The response I got was that no one had evidence of them. However, they didn’t have a firm answer from one of the centers, in Bogovadja, because their computer was broken.

After two days I headed to Bogovadja. The asylum centre was a converted children’s camp facility: swing sets, picnic tables, and brightly coloured jungle gyms dotted the grounds in the middle of a forest close to Serbian army barracks.

It was a nice place, but when I arrived I was crushed—the Syrian family had arrived, stayed the night, and left the next day.

I hope that they found their luck somewhere in Europe, and that they can begin to live and study normally once again. I would love to see them, but this time, I would be the one to say “merci.”