Mali after the coup

Joe Penney

Joe Penney

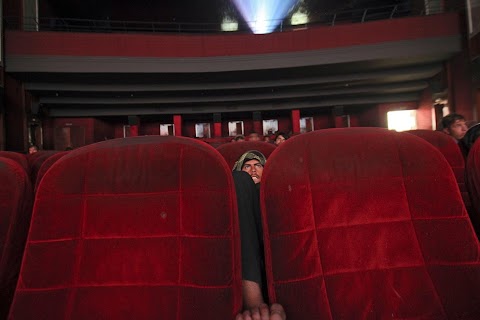

The Grand Mosque of Djenne, a UNESCO World-Heritage listed site famous for its Sudanese-style architecture, used to attract up to 30,000 tourists a year at its peak, according to the local tourist board.

Since the army-backed coup in March 2012, following which Islamist rebels took control of the North, less than 20 international tourists have visited the site.

Mali's tourism industry, concentrated in the areas around Mopti region, which today forms the border between government and jihadist-held territory, was already in decline before the coup over security concerns, and has now completely collapsed.

Tourism provided about 5 percent of Mali's GDP before the security crisis, according to USAID.

But the chaos that erupted in the months since the military staged a coup d'etat has left the country's twin economic engines - the cotton and gold industries - essentially untouched.

Worker Yacouba Traore, 9, shovels cotton seeds at the Malian Animal Feed Company factory in Koutiala.

Mali's cotton sector, which according to CMDT data directly employs four million of Mali's 15 million people, has weathered the crises fairly well.

Workers push barrels of vegetable oil produced with cotton seeds toward a truck at the Malian Animal Feed Company factory.

Gold production, which provides about 15 per cent of Mali's GDP, has stabilised as well.

The days following the coup saw a sharp drop in the stocks of Canadian and South African firms operating in Mali like Randgold, AngloGold Ashanti and Avion Gold Corporation.

An employee of Canadian miner Iamgold watches a football game after work.

But the sector has since rebounded and 2012 national gold output estimates stand at 50 tonnes, said consultant Alhousseini Abba Maiga, against 43 tonnes in 2011.

Adjiatou Beyte, 19, eats lunch at a cafe she works at, located across the road from a joint Randgold-Iamgold mine.

The crisis in Mali has complicated travel, particularly in the north, but the roads south to the coast are unobstructed, allowing free movement of the country's exports.

"The Malians I met were experts at making the best of out of what they had "

When I went to Mali to do a story on how its economy is faring, I wasn’t sure what to expect. The landlocked West African country is currently facing the biggest challenges of its 52-year existence: Jihadist rebels, many of them foreign, occupy its northern two-thirds, while politicians associated with the former regime and ex-coup military leaders squabble over power in the south.

If you just read the headlines, you might think the world has turned upside down in Mali. And indeed in the north of the country, it has: nearly 450,000 people have fled the violence there and now eke out a precarious existence in the south as well as in refugee camps in neighboring Mauritania, Burkina Faso and Niger, according to UN figures. Yet despite the political turmoil, to my pleasant surprise I found out that economically speaking Mali’s lower third — where the vast majority of its 15 million people live — is actually doing quite well.

This situation in the north is a real humanitarian emergency and aid organizations are struggling to keep up. But the industries that form the backbone of Mali’s economy — gold and cotton, both of which are located in the southern third and still under government control — have weathered the storm quite well. Gold miners both large and small-scale are producing as much gold as ever, while good rains combined with high global cotton prices mean that the four million small cotton farmers expect to earn more for their crops at harvest this October than last year.

To me, this situation is striking because it argues against a theory I’ve always thought to be suspect: that economic growth requires political stability. The Malian state — which many of its citizens consider more of a patronage network than a government responsive to its citizens’ needs — has been ineffective for long time. Its collapse has therefore not wreaked the havoc that might otherwise be expected. Besides, the transitional government and the military go out of their way to avoid damaging the growing economy because their quests for political power depend on the state’s coffers.

Being disconnected from their government means that many Malians have some measure of economic insulation from its political instability. But if the situation continues to degenerate, that insulation might wear thin. This is why all Malians I photographed had one common, urgent desire: that the politicians and soldiers sort out their problems so that the average person will not suffer needlessly. Most people I spoke to were against the idea of a military offensive to oust the Salafist rebels in the north, whether led by the Malian army, West African regional troops or Western powers, arguing that the problem can be worked out through dialogue among Malians themselves.

The Malians I met were experts at making the best of out of what they had and helping each other to overcome difficulties they encounter. That kindness and generosity also extended to me, an outsider.

When our team (myself, the Reuters TV stringer in Mali and our driver) arrived in Kalana, the gold mining town we visited near the border with Guinea, we found that all the hotels were booked. But Karim Diakité, a 25-year-old gold mining laboratory technician we met at the restaurant where we were eating dinner, quickly found us an improvised solution: his brother had an empty room at a miners’ encampment and we could stay there. The next day, when our car broke down, Karim was there to help us again, fetching a local mechanic and pointing us to a restaurant.

As helpful as he was, Karim’s was not an isolated case. We felt that level of hospitality, solidarity and knack for problem-solving wherever we went. This is why, more than anything, I came away from this trip with the overwhelming feeling that the answer to Mali’s problems lie in the ingenuity of the Malian people.

Slideshow

An artisanal gold miner peers into a small-scale mine where his colleague is working.

An artisanal gold miner peers up from a small-scale mine where he is working.

An artisanal gold miner tosses a bucket of mudwater to clear the way for work.

An artisanal gold miner takes a rest.

Artisanal gold miner Hawa Siloung and her daughter Sayo watch a colleague pan for gold.

Small-scale gold miners take a break.

Amadou Dabo, a 46-year-old gold buyer, weighs gold.

Small-scale gold trader Amadou Dabo, 46, displays his tools used to weigh and purchase gold, along with roughly seven grams of gold he bought off of small-scale miners for about $30.

Small-scale gold trader Aly Fofana.

Niana (left) and Dramane Diabate, children of gold miners, filter water for household use.

Small-scale gold miner Bangale Sidibe, 29.

Small-scale gold miner Modibo "Fama" Kone, 57.