Not just horseplay

Jorge Dan Lopez

Jorge Dan Lopez

Danger, death and drinking seem to go hand in hand during celebrations for the Day of the Dead in the Guatemalan village of Todos Santos Cuchumatan.

The town marks the festival with a day of drunken horse racing: the culmination of 10 days of boozy revelry in a place where alcohol is usually forbidden.

Slideshow

A man and woman look out of a window during the annual horserace to commemorate the Day of the Dead in Todos Santos.

Locals say that if a rider dies during the race, he will bring a good harvest to the town's farmers for that year.

Men in traditional dress crowd to watch the race, while one man sits down to have a cigarette.

One rider competes in the race, which takes place on an improvised dirt track at the end of town.

Like many of those attending the race, a man wears his hat decorated with coloured feathers.

Tourists and locals gather to watch riders compete.

One man sleeps on the road during the race. The festival is the only time of year that people in the town are allowed to drink alcohol, and many of them celebrate with abandon.

A group of riders takes part in the race.

A rider swigs his beer after having competed.

Riders charge down the track during one of the day’s races.

A man drinks aguardiente after participating in the race.

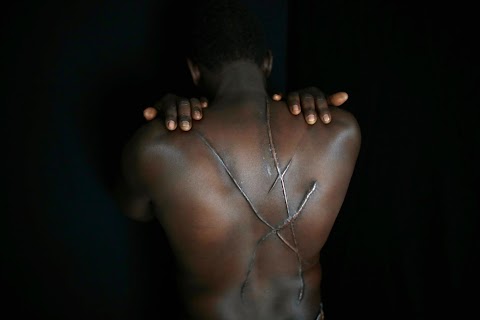

After taking part in the competition, the side of a rider's face starts to swell from an injury he received.

Niches with crosses and candles to celebrate the Day of the Dead are seen on the road to Todos Santos.

“They say that if a rider dies during the horserace, he will bring a prosperous harvest to the farmers in the village that year.”

A drunken horserace on an improvised dirt track at the end of town: this is the grand finale, which rounds off the celebrations of the Day of the Dead - or All Saints Day - in the Guatemalan village of Todos Santos Cuchumatan.

Ultimately, there is much more to the festival than the race itself, and I wished that I had gotten to the town earlier than the morning of November 1, when it takes place. The celebrations had actually begun around 10 days earlier, as did the preparations for welcoming people from neighbouring villages and for competing in the horserace.

First and foremost, everyone began to drink. This the only time that people from the town are allowed to have alcohol; for the rest of the year, there’s a ban on the sale and consumption of alcoholic drinks.

The impression that you get walking around the streets of Todos Santos is that this is a Big Day, the end of a long cycle of celebration. The party has already been going strong for some time.

Overindulgence and lack of sleep have left their marks on many of the town’s residents. Some of them will be the riders in the race that starts at 8 a.m. Many of them, overwhelmed by the booze, “sleep” on the ground in the streets around the racecourse.

It’s 6 a.m. Dawn breaks, and the town is buzzing with activity. Lots of people are drinking coffee, others go to church to leave flowers and pray. The horses are tacked up 50 meters from the spot where the race starts, the riders stick coloured feathers in their hats for decoration and just carry on drinking. They offer me swigs of liquour, and won’t take no for an answer.

I think the brew is stronger than the mezcal spirits that they drink at celebrations and religious festival in my hometown of Guerrero in Mexico. It stings my throat and leaves a burning sensation as it travels down to my stomach.

In a few moments the race will begin. People keep on arriving; great waves of residents from other towns and tourists flood in. There’s not much space to move around, or even to stay in one spot, and being here gets more and more difficult.

As the race begins I keep wondering how this works. How do they decide who has won?

The riders leave in groups. With the blow of a whistle, the authorities from Todos Santos and from other towns signal the moment when they should go, and, after they reach the other side of the track, when they should turn around and come back.

After a few laps, the group changes. Nobody takes note of who gets to the finishing line first or last. It’s just a show of skill - of not falling off during the race from having lost your balance or from the alcohol you’ve drunk - that makes the riders participate. Obviously, religious fervor comes in to it too.

The pattern repeats itself for the next eight hours. They say that if a rider dies during the horserace, he will bring a prosperous harvest to the farmers in the village that year. This time around, no one died, and the race went on and on.