Trucking Brazil's riches

Nacho Doce

Nacho Doce

Brazil is the world's biggest producer of sugar, coffee, citrus and beef and is on the verge of becoming the number one producer of soybeans, but despite all that, it is not an easy place to transport goods.

The truckers who carry the country’s wealth from farm to port grapple on a daily basis with gaping potholes, squalid toilets, dangerous drivers and more.

Traffic bottlenecks like this are one of the problems that truckers deal with, along with backlogs at port and drawn-out bureaucracy. Strained infrastructure is a big problem in Brazil, causing rising transport costs that are getting in the way of the country’s ambitions to become an even bigger global food supplier.

Truck drivers, like these two at a highway restaurant, also face real physical danger on the roads. More than 1,200 truckers lost their lives on Brazil's federal highways last year and one main road in the country has been nicknamed the “Highway of Death”. In an attempt to reduce these accidents, the government recently mandated rest periods for truckers for the first time.

Poor conditions for trucks like this are not just dangerous; they are expensive. The price of hauling a 40-ton load of corn from Brazil’s central savannah to its biggest Atlantic port can cost nearly 40 percent of the value of the corn itself. In the United States, it would only cost about 10 percent of the price of the load to transport it a similar distance.

Standing at a petrol station, driver Paulo dos Santos, his wife and their two children wait for a second day for a new axle to arrive for their truck – one example of inefficiency in the system.

To combat Brazil’s transport woes, President Dilma Rousseff recently unveiled plans to create $66 billion in private investment for roads, rail and other facilities. But investment plans still have to make it through Brazil’s tricky bureaucracy and most new rail projects are still five years away or more. For now, many are in for a long wait.

Slideshow

A truck drives past two others stuck on a highway in the western farm state of Mato Grosso.

A truck driver navigates his way along the notoriously dangerous highway BR-163.

Tire repairman Uilton Gama, 27, stands at his post along a main road.

A cap hangs from a cross to commemorate a road accident victim, beside highway BR-163, also known as the “Highway of Death”.

A worker fills a truck with soybeans in the city of Sorriso, Mato Grosso state.

A freight train filled with cereal grain travels toward Brazil's main ocean port of Santos. Transporting goods by rail in Brazil is more fuel efficient than by truck, but trains can take just as long, and are often full up.

A couple waits for a ride at the side of a highway as trucks pass by.

Brazilian truck drivers negotiate a tight curve along a tough section of highway.

A mass of trucks stand parked as they wait to unload their cereal grain freight.

A truck driver sleeps in a hammock during a break at a truck stop.

A truck driver cooks a meal in his mobile kitchen as he waits to unload his cargo of cereal grain at a rail terminal.

A Brazilian driver reads inside the cab of his truck as he waits to unload his cargo at the rail terminal.

Truck driver Correia, his wife Miriam da Silva, and their 11-month-old son Fhawan Correia, sit inside the cab of their vehicle.

Trucker Marcondes Mendonca waits to get into a parking lot before dropping off his freight of grain.

A truck speeds past shipping containers and a wall showing graffiti of Christ the Redeemer.

"This was the latest of my dream trips – 5,000 kilometres and 10 days spent inside a truck."

As Marcondes walked to his truck, his wife and mother said goodbye with the words: “Be careful and may God be with you.” I knew why they spoke that way; the highway that he was going to take from Rondonopolis to Sorriso in the fertile state of Mato Grosso is nicknamed the “Highway of Death.”

Marcondes and his father, who is also a truck driver, know it very well. It’s the highway famous for frequent accidents, where drivers pay little attention to the law and trucks nearly touch as they pass each other in opposite directions.

I met Marcondes after my interest in the lives of truck drivers had been sparked by a Brazilian movie that I watched about them. Shortly after I saw the film, a Reuters journalist proposed a cross-country trip by truck to report on the cost of transporting Brazil’s riches – soybeans and corn – from the grain belt to the biggest seaport, Santos, on the Atlantic coast.

This was the latest of my dream trips – 5,000 kilometres and 10 days spent inside a truck. I waited as grain cargos were loaded and unloaded, slept in the top bunk inside the cabin, showered and ate in the same places as the truckers, and used the occasional stops to photograph different aspects of the journey.

One of the reasons for our interest in reporting on trucking was to see the results of the government’s new rule mandating that drivers rest for a certain amount of time. The goal is to limit the number of hours that truckers drive without sleeping, and to reduce accidents.

At our first rest stop with Marcondes, who heeded this new rule, I photographed another driver sleeping in a hammock that he tied to his truck. As I took some pictures, he asked me what I was doing. When I explained, he said: “Tell President Dilma Rousseff that truck tires are not square. I don’t think she’s ever been on these roads.”

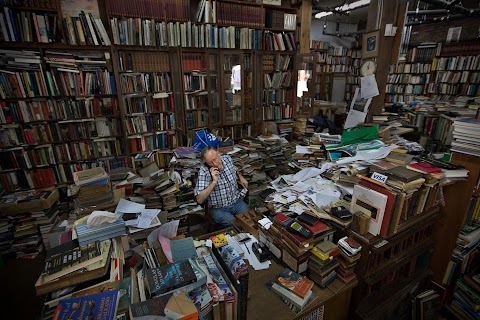

One of our longest stops was at a cargo terminal where grain was transferred from trucks to train wagons. It was a 12-hour wait for each truck to unload, so I had the chance to meet lots of people. They were open, talkative, and willing to be photographed, even in the hot wind that swirled around us in clouds of dirt.

There I met Chiquinho, a 66-year-old trucker who was dressed like a gentleman on his way to a fine restaurant, but who was cooking a meal in a makeshift kitchen under his truck. I commented on his smart outfit, and he said, “Son, I’ve been inside that truck too long.” Then he invited me to eat right there with him.

There were drivers travelling with their families, drinking coffee next to their vehicles as they waited. One group of truckers, who hoped I would show the government what their lives were really like, asked me if I knew a saying that is common in Mato Grosso. When I said I didn’t, one of them told me: “Mato Grosso satisfies Brazil’s hunger, and provides for the world.” It sounded like the perfect way to explain Brazil’s agricultural power, especially in a year when Brazilian production helped fill a gap left by a record drought in the United States.

The next night we reached the mountains above the port of Santos. Marcondes was at the limit of the number of hours he was allowed to drive according to the new legislation. I was tired just from being a passenger, and I could imagine how he felt driving. But the only truck stop we could find with a parking lot had a big sign outside reading: “Full.” I looked at Marcondes and he said, “It’s impossible to stop along the side of the road. Let’s continue to Santos. The new rules don’t work here.”

There was no place to rest and there was a real danger of being assaulted or hijacked on the road. Thankfully though, we reached Santos, where the mess of trucks in the parking area was incredible. Hundreds of trucks were sitting there, with a full day to wait before they would be able to unload.

We were close to the end of the trip, and I showered in the truckers’ area, where the conditions were horrible, with rats running wild everywhere. Marcondes was scheduled to unload at 8a.m. the next morning, 24 hours after arriving. A lot of that time was spent doing paperwork.

This trip was a wonderful experience in every way. After saying goodbye and thanking Marcondes I had to hitch a ride in another truck towards Sao Paulo. On the last leg of my trip to reach the airport, I purposely climbed onto one of the motorcycles that serve as transportation, instead of getting into a regular taxi. I was hoping to get a little dirty. I actually wanted to arrive home in the same dusty condition as when Marcondes and I reached our destination the day before.

My adventure was complete.