Sick and in crisis

After religious violence forced many of Myanmar’s Muslim Rohingya minority from their homes, the community is now grappling with a health crisis exacerbated by restrictions on international aid.

In February, Myanmar's government expelled Medecins Sans Frontieres-Holland, the main aid group providing healthcare to more than half a million Rohingya in Rakhine State. Other NGOs have also had to halt their work.

Attacks on NGO and U.N. offices by a Rakhine mob in March led to the withdrawal of groups giving healthcare and other essential help to many thousands of Rohingya displaced by Buddhist-Muslim violence since 2012 and now living in camps like the one pictured above.

Medecins Sans Frontieres-Holland (MSF-H) was barred by Myanmar authorities after the group said it had treated people believed to have been victims of violence in southern Maungdaw township, near the Bangladesh border, in January.

The United Nations says at least 40 Rohingya were killed there by Buddhist Rakhine villagers. The government denies any killings occurred.

The government had pledged to allow most NGOs to return to full operation after the end of Buddhist New Year celebrations this month but so far only food distribution by the World Food Programme has gone back to normal.

In the image above, a group of Rohingya wait to receive their share of food aid at a camp for internally displaced people.

Rakhine community leaders in the state government's Emergency Coordination Centre have imposed conditions on other aid groups wanting to return.

NGOs will only be allowed to operate if they show "complete transparency" in disclosing their travel plans and projects and are not seen to favour Rohingya, said Than Tun, a Rakhine elder who is part of the centre.

With foreign aid largely absent, members of the Muslim minority are struggling.

Gorima Khatu’s three-month-old daughter Asoma died of fever and diarrhoea at a dusty camp for internally displaced people.

"I think my child would have made it if someone was here to help," Asoma's mother, Gorima, told Reuters, as she cradled the girl's shrouded body.

Visits by Reuters to several camps reveal a widespread struggle with illness. The severely malnourished 25-day-old twins, pictured above at the Dar Paing camp, are one example.

Government medical teams have been making limited visits to Rohingya areas, but foreign aid organisations say they are inadequate. Most of the slack has fallen to under-qualified Rohingya using whatever is at their disposal.

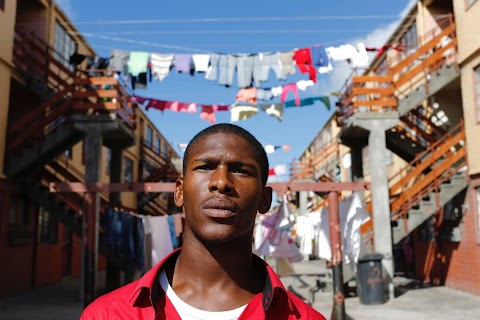

In Kyein Ni Pyin (pictured above) nearly 4,600 Rohingya live under police guard and their movements are restricted. They are classified by the government as illegal Bengali immigrants.

Win Myaing, a spokesman for the Rakhine State government, dismissed the notion that there is a health crisis in such places.

"There is a group of people in one of these camps that shows the same sick children to anyone who visits. Even when the government arranges for treatment they refuse it," he said.

The United States, Britain and other countries have called on the government to allow aid groups to return to Rakhine State, to little effect so far.

Slideshow

Children play in the fields near the Dar Paing camp for internally displaced people in Sittwe, Rakhine state.

Rohingya women stand in the Kyein Ni Pyin camp for internally displaced people.

Rohingya women and their children wait to receive treatment at a makeshift clinic at Thet Kae Pyin camp.

A Rohingya woman holds her baby, who is suffering from a skin infection, at the camp.

A displaced Rohingya girl is pictured in Kyein Ni Pyin.

Tin Aung Zin, a nine-year-old Rohingya boy in a coma which his mother says was caused by shock during communal violence in their former neighbourhood, lies on the floor inside their new home at a village near the Thet Kae Pyin camp.

A boy holds his severely malnourished sibling in his room at the Dar Paing camp.

The body of three-month-old Asoma Khatu, who died of fever and diarrhoea, is covered with a piece of white cloth at the Kyein Ni Pyin camp.

Muhammad Ali, a 54-year-old Rohingya man who has suffered from tuberculosis for over a year, lies inside his room at the Thet Kae Pyin camp.

Muhammad Alam, who was suffering from a diarrhea for over a week, lies on a mat in front of his room.

Rohingya people receive their share of food aid from the World Food Program at the Thae Chaung camp.

Rohingya women hold their children at the Khaung Dokkha camp.

Musana Khatu, a 22-month-old Rohingya girl suffering from diarrhea, is examined after her mother brought her to a makeshift clinic at the Thet Kae Pyin camp in Sittwe.

A Rohingya woman shows her baby to a nurse as another woman is examined by a doctor from the Ministry of Health at a hospital near the Dar Paing camp.

Medicine is spread out at a pharmacy, which also serves as a makeshift clinic at the Thae Chaung camp.

A sick Rohingya boy waits to receive medical treatment at an improvised clinic.

Kyein Ni Pyin camp for internally displaced people is pictured through the windows of an empty building.