Fishing in Fukushima

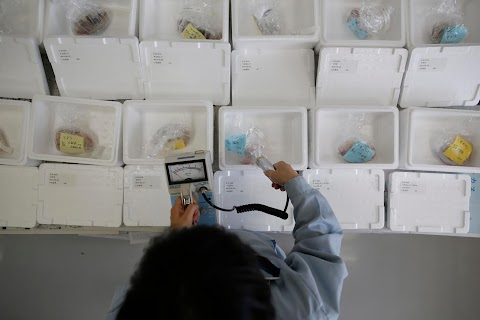

A laboratory technician uses a Geiger counter to measure radiation in fish caught close to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, crippled by a devastating 2011 tsunami.

Commercial fishing has been banned near the nuclear complex since the disaster two years ago, and the only fishing that still takes place there is for contamination research and is carried out by small-scale fishermen contracted by the government.

Story

Rising radioactive spills leave Fukushima fishermen floundering

Dozens of crabs, three small sharks and scores of fish thump on the slippery deck of the fishing boat True Prosperity as captain Shohei Yaoita lands his latest haul, another catch headed not for the dinner table but for radioactive testing.

Japan's government banned commercial fishing in this area, some 200 km (125 miles) northeast of Tokyo, after a devastating 2011 tsunami and the reactor meltdowns and explosions that followed at the nearby Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

The plant's operator, Tokyo Electric Power Co, or Tepco, has battled since then to keep radioactive water used to cool the crippled reactor from leaking into the ground and the sea.

The walls of a once-bustling fish market that sold Yaoita's catch of flounder, rockfish, greenling and other sealife in the port of Hisanohama, about 20 km (12 miles) south of the ruined plant, remain in ruins.

The fishermen of Hisanohama, forced out of work by the disaster, have had no choice but to take the only job available - checking contamination levels in fish just offshore from the destroyed nuclear reactor buildings.

"We used to be so proud of our fish. They were famous across Japan and we made a decent living out of them," said 80-year-old Yaoita, who survived the tsunami by taking on the waves and sailing the six-person True Prosperity out to sea.

"Now the only thing for us is sampling."

Shoulders stooped from years of hard work, Yaoita is happy to be back pulling fish out of a 300-metre (330 yards) net. Like many younger fishermen, he's unsure how long he can stay at it.

The fishermen and Tepco are in dispute over the utility's plans to dump 100 tonnes of groundwater a day from the devastated plant into the sea. The complicated clean-up plan for Fukushima could take 30 years or more.

Tepco's challenge is what to do with the contaminated water that has been pooling at the plant at a rate of 400 tonnes a day - enough to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool in a week.

So far it has been racing to build tanks to store the contaminated water on the grounds of the plant, in which all the water is kept at the moment.

It has also asked fishermen to support a plan to build a "by-pass" that would dump groundwater into the sea before it becomes contaminated by flowing under the reactor's wreckage.

"We are staunchly against it," said Tatsuo Niitsuma, 71, who fishes with Yaoita.

MORE CONTAMINATION, LESS HOPE

Representatives from fishing cooperatives met Tepco officials on Thursday to discuss the proposal, with Trade Minister Toshimitsu Motegi to instruct Tepco on what to do, although no final plans were announced.

In addition to the "by-pass" Motegi, who also holds the energy portfolio, told Tepco to create "protective walls" in the ground by freezing the soil around the reactors to create an underground barrier to stop groundwater from flowing in and mixing with contaminated water inside the reactor building.

The fishermen, however, worry the "by-pass" plan risks more contamination and delays, possibly ending any hope for the only job they know.

Tepco officials have said it may take as long as four years to fix the problem, but have said they do not need outside help.

The uncertainty and stress have become problems. Many former fishermen live in temporary homes next to people they barely know after losing not only their jobs, but also family members.

Waves as high as 40 metres wrought havoc across several hundred kilometres of Japan's northeastern coast, damaging ports handling 7 percent of the country's industrial output, some 28,500 ships and 319 small fishing communities like Hisanohama.

The total cost of damage to the fishing industry is estimated at around 1.26 trillion yen ($12.49 billion).

About 40 Hisanohama fishermen survived the disaster. They could make a few thousand dollars a month each with good catches, but instead get by on handouts for tsunami survivors.

"For many middle-aged men, their work meant everything, so now they find it hard to mingle with others, cut themselves off and start drinking," said Hideo Hasegawa, who runs a support centre in a 3,000-strong temporary housing settlement.

The fishermen's opposition to Tepco's plans underlines deep distrust across radiation-contaminated areas towards Tepco and the government after their uncertain response to the disaster, and a lack of clear information about radiation risks since.

"They say it's safe, but they had always told us that the nuclear power is safe too - and just look what a mess we've gotten ourselves into because of that," Yaoita said.

Many fish caught in the area test below Japan's limits on radiation, a figure of 100 Bequerels per kilogram of Caesium-137 and Caesium-134, according to theJapanese government. However, crews say fish that live near the sea-floor, such as cod, halibut or sole, often test for excessive levels of radiation.

A large crab caught by Yaoita before the disaster could fetch as much as $30 on the Hisanohama market. A kilogram of flatfish could sell for about the same. Once he could catch dozens of both and many other fish on a single morning outing.

"The nuclear disaster destroyed our livelihoods and now we are like beggars," said Yaoita.

"Previously I never went to see the doctor. Now it feels like I down more drugs and medicine than actual food."