The only kid in the school

David Mdzinarishvili

David Mdzinarishvili

Bacho Tsiklauri is an ordinary nine-year-old schoolboy, but in his class he really stands out: he is the only child there.

Bacho is the sole pupil at his local primary school in the tiny Georgian village of Makarta, located in a remote mountain gorge some 100 kilometres (62 miles) north of the capital Tbilisi. The village has around 30 residents including four children: three older ones who attend high school in a neighbouring village and Bacho himself.

Slideshow

Bacho leaves his home for school in the morning.

He walks to class with his father Gia.

Bacho waits for his teacher in front of the school, which is a room on the second floor of a private house in the village.

He listens to his teacher during class.

A register with only one name, "Bacho Tsiklauri," lies open at the school.

Bacho rests his chin on his hands in class.

He listens to 47-year-old Lia Tsiklauri, who teaches him Georgian and mathematics. She attended the same primary school herself when she was a child.

Bacho stands in front of the chalkboard and listens to his teacher Lia.

He writes on the board during class.

Bacho writes out exercises during his English class.

He stands by himself in the school yard at recess.

He leans against the wall back at home.

Bacho looks out of the window in his house.

He walks through a room where his father Gia, 51, sits smoking.

Bacho's mother Lela Machkhashvili, 39, helps him with his homework.

"Of course, it was always Bacho who performed all the tasks, Bacho who answered all the questions, and Bacho who came to the board."

Bacho Tsiklauri is a normal nine-year-old boy, no different from any other child his age, and he wouldn't stand out in a schoolyard among other third-year students. But in his school he does stick out because there are no others: Bacho is the only child at elementary school in the Georgian village of Makarta.

I heard about Bacho by chance, and I wanted to meet him to find out what it is like to be the only kid in the classroom and the only one in the school.

The journey from Georgia’s capital Tbilisi to Makarta is 100 kilometers (62 miles), including 80 kilometers on one of Georgia’s main roads. The remaining 20 kilometers is on a dirt track through the Gudamakari gorge, and covering this leg of the trip took me about the same amount of time as the first stretch. This is the road that separates Makarta from the rest of the country.

In the village, which stands on the slopes of the gorge, you can see an abandoned two-storey house, which was once the pride of its owners. It is one of several abandoned homes, left behind by those who went to look for a better life in more developed parts of the country. Now the community is home to around 30 people including four children: three older ones who attend high school in a neighbouring village four kilometers away, and Bacho, the youngest, who goes to the local primary school.

The first time I came to see Bacho I arrived at 7a.m. and found him awake and preparing breakfast. Afterwards, he got on with his homework along with his mother Lela and older brother Dato, who goes to school in the nearby village. Dato needs an hour to get to school, so he leaves the house much earlier than his brother.

I used the remaining time before the beginning of the school day to try to get acquainted with Bacho. I asked how he spent his spare time, but he was just interested in my photography equipment:

“What do you do after school?” I asked.

“Nothing special. Can your camera shoot pictures of the top of that mountain?” he replied.

“When you grow up, who do you want to be?” I continued.

“I don't know. And your camera can shoot at night?”

I gave up. We discussed my camera and Bacho even took a few shots.

By 10 a.m., Bacho was standing at the window and began to watch the school building, looking out for his teacher Lia Tsiklauri walking to school.

As soon as she appeared, Bacho left the house and started down the winding road to class.

The school is located in a room on the second floor of a private house. It used to be bigger, but now this is plenty of room. In the courtyard, we met 47-year-old Lia, who teaches Georgian and mathematics and who studied at the school herself as a child.

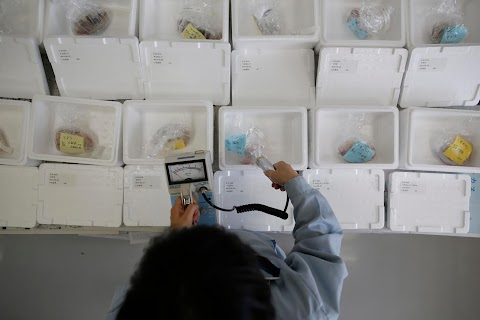

In the classroom, there are desks for four students, a wood stove stands under the cracked window and various school supplies hang on the brick walls.

At the beginning, I saw that the teacher and student didn't feel comfortable with me being there: having a third person in the class, and one with a camera, was an unfamiliar situation.

Lia began the lesson by taking the register, but then she laughed and with this the tension disappeared. They soon forgot about my presence, and the class went as usual: checking homework, going over previous lessons, being called to the board, and learning new material.

Of course, it was always Bacho who performed all the tasks, Bacho who answered all the questions, and Bacho who came to the board. He couldn't get out of it, and there was no one to whisper the answer if he didn’t know – although I don’t think he needed the help.

During the break, Bacho went out into the yard. He kicked a half-flat football a couple of times, and walked a few laps around the little area. He was obviously bored but then his second teacher, 40-year-old Inga Chokheli, arrived and he livened up again. The English lesson began.

Both the teachers praised their only student. They just had one disappointment: Bacho was their last pupil and when he goes to high school in the nearby village, the primary school in Makarta will close.

Bacho plays on the top of a hill by his home in Makarta.