Going underground

Lucy Nicholson

Lucy Nicholson

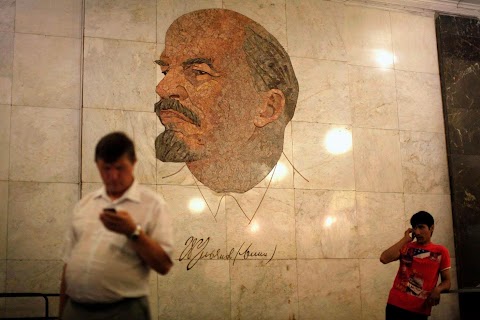

An image of former Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin seems to gaze down sternly as two men use their mobile phones at the Biblioteka Imeni Lenina station, part of Moscow’s sprawling and historic metro system.

Built under Stalin and opened in 1935, the Moscow metro is an extravagant gallery of Communist design, featuring Soviet artworks, statues, chandeliers, stained glass and ceiling mosaics.

A woman walks down the platform as a train arrives at Mayakovskaya metro station, opened in 1938 and named after the Soviet writer Vladimir Mayakovsky.

With elements constructed from marble, limestone and pink and grey granite, the station is also decked out with a set of ceiling mosaics, depicting “24 hours in the land of the Soviets”.

Although much of its architecture evokes the past, the Moscow metro is very much still a vital and functioning part of the city. It transports 7 to 9 million people a day, with a single ride costing 30 Rubles, around $1.

Slideshow

A Soviet themed panel adorns the ceiling in Novoslobodskaya metro station, which was opened in 1952.

Two men wearing matching shirts travel down an escalator.

A woman reads a magazine as she leans against a wall at Chistye Prudy metro station in central Moscow.

A driver pulls into Biblioteka Imeni Lenina station.

Passengers walk towards a train.

A man and woman hug in front of a stained glass panel in Novoslobodskaya station.

A couple embraces on the metro.

Another couple shares a pair of earphones as they listen to music together.

Two couples ride on the metro.

Women read a book together as they sit in a carriage.

Passengers take a late night metro.

A crowd of passengers walks through Prospekt Mira station.

People walk by the entrance to Arbatskaya metro.

"During the Cold War, stations on the Arbatskaya line with plodding wooden escalators, were dug deep to serve as shelters in the event of nuclear war."

London has the world’s oldest underground rail system; Tokyo’s metro has employees to push people into packed trains; New York’s subway is an ethnic melting pot. But hidden beneath the streets of Moscow is something completely different.

To step onto the Moscow metro is to step back in time and immerse yourself in a museum rich in architecture and history, complete with Soviet artworks, Art Deco styling, statues, chandeliers, marble columns and ceiling mosaics.

We were given metro passes with our credentials when we arrived to cover the IAAF World Athletics Championships in Moscow. On the first day, I caught the metro back to our hotel with a group of Reuters photographers, when we missed the last media bus.

We were wowed by the architecture, and continued to travel this way to photograph both the metro and the people riding it: couples kissing, drunks taking late trains home, average commuters doing their best to avoid eye contact.

The trains were incredibly noisy, and it was difficult to hold a conversation while in a carriage. But they were also incredibly prompt. If we missed a train, rarely did we have to wait more than a minute for another to arrive.

It was best to rush onto a train when it first pulled into the station, to avoid the moment when the driver closes the doors on stragglers. I only made this mistake once, the heavy doors bouncing off my forearms, before aggressively snapping shut.

Locals said we were experiencing the metro during the only tolerable empty time of year: August is when many Muscovites are on vacation. A Russian photographer told me that after the Soviet era, people tended to be wary and suspicious of being photographed.

But wearing our World Athletics backpacks, we clearly looked like tourists, and people generally ignored our presence. A rare few smiled; a couple of children borrowed their mother’s iPhone and photographed us back. Only a train driver responded angrily sounding a deafening horn that echoed through the station when I tried to photograph him.

Theft is common on the metro, despite the ubiquitous presence of security cameras and police, so we always stayed together as a group when carrying our cameras.

One of the most beautiful metro stations, Mayakovskaya, is famous for its 34 ceiling mosaics depicting “24 Hours in the Land of the Soviets.” During World War II, it was used as a command post for Moscow’s anti-aircraft regiment.

At Ploshchad Revolyutsii station, as each crowd of people hurtles off the train, a throng of hands reaches out to rub the nose of a bronze dog to bring them luck. The dog’s nose has been polished shiny, and stands out among the 76 life-size bronze sculptures in the dark station.

During the Cold War, stations on the Arbatskaya line with plodding wooden escalators, were dug deep to serve as shelters in the event of nuclear war. Rumor has it that in the 1950s, Stalin ordered a top-secret line dug deeper than the other metro lines, linking the Kremlin to the airport and a series of nuclear bunkers.

Lenin’s face is everywhere; Stalin’s was removed in 1956, three years after his death. Nikita S. Khrushshev’s de-Stalinization program sought to remove references to the dictator responsible for the deaths of millions of Soviet citizens, through forced collectivisation, deportation of ethnic groups, imprisonment in the Gulag, and party purges.

A ceiling panel in Belorusskaya metro station, which shows three women holding a hammer and sickle wreath, with the letters CCCP, originally depicted the women reaching to touch a bust of Stalin.

Only recently under Putin, have more favourable references to Stalin crept back into the patriotic narrative of World War II. A 2009 renovation of Kurskaya station, surprised people with its inclusion of the words of the Soviet anthem as it used to be sung under Stalin: “Stalin reared us — on loyalty to the people. He inspired us to labor and to heroism.”

In a country with a modern history so laden with violent upheaval, there is a fine line between reconstructing and celebrating the political undertones of the rich architectural heritage. “He who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past,” wrote George Orwell in his novel ‘1984’.