The ghost villages of Verdun

Vincent Kessler

Vincent Kessler

Nearly a century after the guns fell silent in World War One, a group of villages wiped out by fighting on France's bloodiest battleground lead a ghostly existence.

Their names still appear on maps and mayors representing them are chosen by local authorities. But most of the streets, houses and people who once lived around the French stronghold of Verdun are gone. Empty space and war memorials have mostly taken their place.

Before & After

Before: An old postcard shows the settlement of Louvemont before it was destroyed. Louvemont was one of nine villages that were annihilated during the Battle of Verdun, which raged for months on a 24-km (15-mile) front around hill-top fortifications, which French commanders had decided to defend at all costs.

After: After the First World War ended the French government bought up 10,000 hectares of battleground around the destroyed villages – land riddled with shell fragments, unexploded ordnance and deeply buried corpses – and declared it permanently off-limits for construction. Today, Louvemont is entirely uninhabited although like the other destroyed villages it still has symbolic administrative existence and is represented by its own mayor, keeping the memory of its former life alive.

Before & After

Before: A picture shows Ornes before the fighting of 1916 that wiped out the village.

After: Now, the area is dotted with eerie reminders of once-thriving life, such as this sign by an empty road telling visitors they are entering Ornes. Although the old village was destroyed during the war and has not been rebuilt, part of its territory spills outside the battlefield zone where new construction was banned. Today, a few people do live within its bounds and can vote there in the upcoming local elections.

Before & After

Before: A postcard shows the village of Fleury, close to Verdun, before 1916.

After: A recent photograph shows the area as it looks now. According to the village's mayor, at one point during the battle of Verdun some 90,000 tons of bombs hit Fleury in a single day.

Before & After

Before: A picture shows the village of Ornes in 1916, after the first German offensive. By the end of the battle that dragged from February to December, 300,000 French and German soldiers had been killed and more than 450,000 injured.

After: Today, the village stands mostly empty, and the landscape is scattered with a few columns and broken stones.

Slideshow

Memorial crosses stand in rows at the World War One ossuary of Douaumont, close to Verdun.

Francois-Xavier Long, the 69-year-old mayor Louvemont, poses in his village.

A stone marks the place where a cafe once stood in the village of Fleury.

Jean-Pierre Laparra, 62, mayor of Fleury, poses in his village.

Light shines through the trees in Fleury, near Verdun.

Charles Saint-Vannes, 77, mayor of Ornes, poses in the remains of the church of his village.

A road sign reads "main street" in the village of Bezonvaux.

Jean Lavigne, the 72-year-old mayor of Cumieres-le-Mort-Homme, poses in his village.

A monument dedicated to the First World War stands in Verdun.

"It is very hard when you arrive in the area now to have any idea of what the countryside looked like before the war."

The year 2014 brings together the past and the future for France. It is a time of local elections, and it is also the hundredth anniversary of the start of the First World War.

The Battle of Verdun in northeastern France was the longest battle of the so-called Great War, lasting some ten months from February to December 1916. It was also one of the most murderous.

After the 1870-71 war between France and Prussia, which ended with the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine by the Germans, Verdun was at the eastern edge of France. The city was fringed by hills – hills in which a network of forts were built to protect the border.

During the First World War, the Germans wanted to make a massive attack on a target that had great historic significance for the French, and they thought that weakening France around Verdun could change the face of the war.

On February 21, 1916 they started the assault with a huge bombardment. A charity named “The Western Front Association” writes that during the initial stage of the Battle of Verdun, Germany fired more than a million shells.

Ten months of fighting saw German and French troops being pushed back and forwards, and by December 1916 the French had retaken almost all the territory that had been lost. German troops did not come through, but nine villages had been utterly wiped out. An estimated 300,000 French and German soldiers were killed and over 450,000 were injured.

It is very hard when you arrive in the area now to have any idea of what the countryside looked like before the war. People say that each square meter of the battlefield was hit by a shell and the village of Fleury alone was struck by 90,000 tons of bombs in one day, according to its mayor. Most houses were completely destroyed; their former locations are now marked only by signs.

The bombings sculpted the landscape, pockmarking the ground with craters. The area was later designated a “red zone” meaning that any construction or digging was prohibited, since the ground had been left filled with tons of leftover shells and ammunition, as well as bodies of those who died.

After the war, it was decided that the villages should not be rebuilt, and most have remained without any inhabitants. But nonetheless they are still administered by unelected mayors, who are chosen by local authorities after a law was passed in 1919, symbolically maintaining their administrative existence.

To be designated as the mayor of one of these villages, “candidates” must send a letter to the local authorities, explaining why they want the post. For the most part, family history and a sense of attachment to the villages is the reason for a mayor’s selection. Being designated a mayor has also become a family tradition for some, passed down from grandparents to children or grandchildren.

Francois-Xavier Long, a doctor from Verdun, became Mayor of Louvemont after proving his great interest in history and military medicine. His village is completely uninhabited.

The village of Ornes, on the other hand, is located on the very edge of the “red zone” and part of its territory spills over to the other side. Though the village proper was destroyed and has not been rebuilt, there are now a few people who live just outside the "red zone" within its bounds. This means that after simply having been selected as mayor for the past decade, Charles Saint-Vannes will actually face his first proper election in 2014. He was born in his village and, as the Mayor of Ornes, is the successor to his father and mother.

After learning about all these battles, bombings and deaths, discovering these hills shaped by war, and seeing the monuments dedicated to soldiers, the most surprising thing I noticed as I walked through these villages was the feeling that they gave me. It was a feeling of peace.

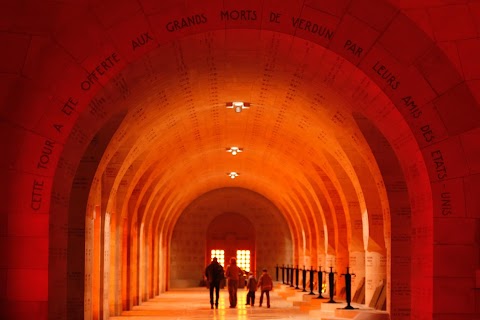

A World War One memorial stands in Douaumont.