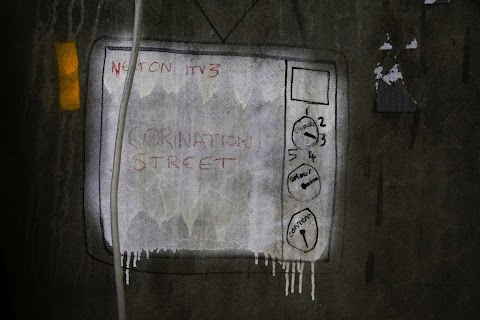

White poverty in South Africa

Finbarr O’Reilly

Finbarr O’Reilly

While most white South Africans still enjoy lives of privilege and relative wealth, the number of poor whites has risen since the end of apartheid.

Lukas Gouws, 29, is one of them.

He lives in a squatter camp for poor white South Africans called Coronation Park. A shift in racial hiring practices since the end of apartheid and the global economic crisis means many white South Africans have lost their jobs and their homes and are living in camps like this one.

Children play with a tyre used to block the entrance to the squatter camp.

Slideshow

A woman looks out the window of her one-room hut.

Lukas Gouws (centre), 29, scolds a boy for digging up snakes.

A girl stops by a neighbour's fireplace before she walks to school.

Desmond Thomas, 40, (right) lights a cigarette beside the charred remains of his caravan that burned down the previous night after a candle set it on fire.

Andre Coetzee, 57, sits with a neighbouring family at a squatter camp.

A man receives a monthly supply of donated food aid.

A woman pushes a cart with a monthly supply of food aid.

Residents line up for a communal meal.

A family smokes together during a quiet moment.

Leone Smit, 41, cleans dishes in her shack while her son and his friend rest on a bed.

Andre Coetzee, 57, drinks a mug of coffee.

A girl cries after being beaten by her father, in their makeshift home.

Vincent Abbott, 42, enjoys an evening smoke as his wife Esther Botha, 41, knits on their bed inside their small single-room hut.

A girl puts her hair in a pony tail as she gets ready to walk to school.

Girls walk to school barefoot.

Friends talk through the window of a one-room hut.

Accountant Vernon Nel checks his email on generator-powered computers using a wireless modem in a tented home attached to caravan that he shares with six other people.

Girls set up a play house in their garden outside a family shack.

Anne Le Roux, 60, calms down her grandson, Reynard, 14.

Vernon Nel (left) cuts the hair of Reynard.

Children walk through the squatter camp.

Rudolph, 12, does his homework in the kitchen of his family's shack.

A woman drives a car in the squatter camp.

People attend an Afrikaans Sunday service in a makeshift tent church.

Donovan Durant, 23, carries the casket of his baby who died hours after being born prematurely while his girlfriend Anna Snyders, 20, (left) is comforted during the funeral service.

Anna Snyders grieves beside her boyfriend, Donovan Durant, at the funeral for their baby.

"Cats and dogs roam noisily through the settlement, which is strewn with heaps of rubbish, scrap metal and car parts."

Sitting in a deckchair at a South African squatter camp, Ann le Roux, 60, shows me a yellowing photo from her daughter’s wedding day. Taken not long after Nelson Mandela became the country’s first black president in 1994, it shows Le Roux standing with her Afrikaans husband and their daughter outside her home in Melville, an upmarket Johannesburg neighbourhood. Sixteen years later, she shares a caravan and a tent with seven others, including her daughter and four grandchildren, at Coronation Park – a squatter camp for poor white South Africans.

I spent a week at the camp in Krugersdorp, photographing residents and examining the politically sensitive issue of white poverty. While most white South Africans still enjoy lives of privilege and relative wealth, the number of poor whites has risen since the end of apartheid. Le Roux had to sell her house after her husband died. She lost her job as a secretary at the city planning council — where she had worked for 26 years — after she took time off work to recover from her husband's death. “They wouldn’t take me back because of the political situation,” she says, looking down at the fading photo.

Seeking to reverse decades of inequality, the ruling African National Congress government has introduced laws that promote employment for blacks and aim to give black South Africans a bigger slice of the economy. This shift, coupled with the effects of the global financial crisis, means many less fortunate white South Africans have fallen on hard times. According to civil organisations and the largely white trade union Solidarity, there are approximately 450,000 whites living in squatter camps. Around the capital Pretoria alone there are 80 such settlements.

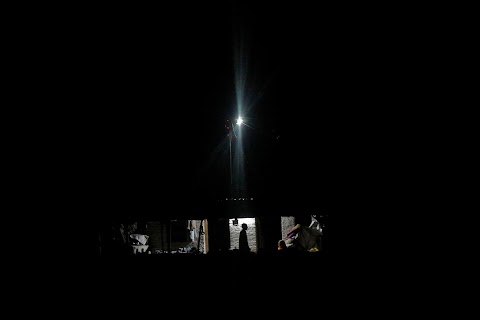

Ringed by yellow hills of earth dug up by generations of gold miners, the park was used by the British as a concentration camp for Afrikaners during the Anglo-Boer war. Now it is home to over 400 whites squatting in tents and caravans. Cats and dogs roam noisily through the settlement, which is strewn with heaps of rubbish, scrap metal and car parts. The council wanted to develop the area into a site for viewing televised soccer during the 2010 World Cup; however, after failing to evict the squatters, they instead cut electricity to the camp. Now water is heated and food cooked on open fires.

Formerly comfortable Afrikaners recently forced to live on the fringes of society see themselves as victims of “reverse-apartheid” that they say puts them at an even greater disadvantage than the millions of poor black South Africans. “Blacks get more than whites at the moment. They’re being pulled forward against us. That’s why all of us are here. It’s very unfair because they told us it was going to be equal, but it’s not equal,” says Dennis Boshoff, 38.

This feeling of victimisation and abandonment by the state has forged at the camp a collective sense of fatalism, isolation and firm reliance on their Calvinist religion. Each of the camp’s ramshackle huts and tents is adorned with religious paraphernalia and contains an Afrikaans-language Bible. Many poor white communities also struggle with alcoholism, violence and abuse.

Few have been more devastated by social and economic change in the new South Africa than the growing number of poor whites. Under apartheid, which was introduced in 1948, the weakest and least educated whites were protected by the civil service and state-owned industries operating as job-creation schemes, guaranteeing even the poorest whites a home, usually with a swimming pool. With that safety net now gone, unskilled whites find themselves on the wrong side of history, gaining little sympathy from those who perceive them as having profited unfairly during the brutal apartheid years. "Our colour here is not the right colour now in South Africa," Le Roux says.

The sun rises over the squatter camp.