Losing the land war

Three-year-old Sandriely cries in front of the hut where she lived before it was destroyed by a fire set by an unknown arsonist. It was part of a makeshift camp, home to an indigenous Guarani Kaiowa community living squeezed between a highway and their ancestral land.

The attack came as members of Brazil's Guarani tribe are suffering from an increasingly bloody conflict with farmers over traditional territory.

This hut is part of a Guarani Kaiowa makeshift camp, sandwiched between highway BR 463 and their ancestral land, known as Tekoha Apika'y. Members of the indigenous group have been living here since 2009, after they failed to take back the territory from farmers.

The Guarani community as a whole, with a population of around 50,000 divided among the Kaiowa, Ñandeva, and Ava sub-groups, is suffering greatly from an on-going and bitter struggle to return to their traditional territories.

The conflict has the characteristics of a land war, in spite of Brazil's indigenous policy being considered one of the most progressive in the world.

Guarani Ava spiritual leaders perform a healing ritual in a house of prayer on their ancestral territory, which they call Tekoha Yvoh'y.

Despite the Guarani population’s struggle over land, they have managed to preserve their native language and their religion, practiced regularly in rituals and collective prayers.

Slideshow

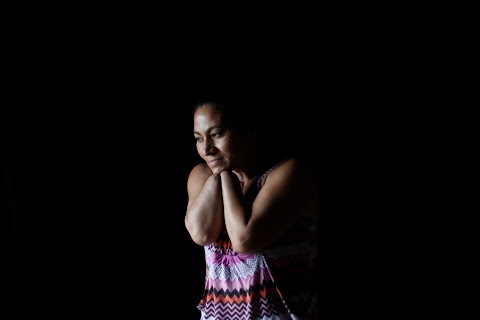

Guarani Kaiowa woman Dilcia Lopes and her children live in the ramshackle camp on the strip of land between highway BR 463 and their ancestral territory, which they call Tekoha Apika'y.

Dilcia Lopes and her children watch a truck pass by on the highway.

A banner hung by a group of Guarani Kaiowa reads, "Enough of killing indigenous," on the edge of ancestral territory known to them as Tekoha Ita'y. Last April a farmer who occupied part of their land attacked them, but died in the confrontation.

Amnesty International's Secretary General, Salil Shetty (3rd left, dark blue shirt), meets with members of the Guarani Kaiowa community at the makeshift camp where they live.

Amarilda Carvalinda, a 35-year-old Guarani Kaiowa woman, stands in her home.

Paulina Takua Rokavy (right), a member of the Guarani Ava group, teaches children in an improvised school on the edge of ancestral land known to them as Tekoha Yvoh'y.

Guarani Ava children have a lunch of peanuts and chica, a drink made from cassava, at their home.

Guarani Kaiowa children swim in a pond next to a highway that runs past their historic territory, called Tekoha Boqueron.

A Guarani Kaiowa boy stands in front of his makeshift home on the edge of the ancestral land they call Tekoha Takuara. The group's chief, Marcos Veron, was shot to death in 2003.

Guarani Kaiowa tribespeople gather at the place where Denilson Barbosa, a 15-year-old member of their group, was killed by a farmer.

Guarani Kaiowa people gather at the cross marking the place where 15-year-old Barbosa was killed.

A Guarani Kaiowa boy walks past roadside vegetation after a fire set by an unknown arsonist ravaged their makeshift camp.

Members of the Guarani Kaiowa community look at their hut, which was destroyed by a fire near their ancestral land called Tekoha Apika'y.

Relatives of assassinated Guarani leaders attend this year's Aty Guasu, or Great Assembly, that brings together their chiefs and spiritual leaders in Jaguapiru village, Mato Grosso do Sul state.

Guarani leaders and chiefs raise their Mbarak, a type of traditional rattle, during what they called a "war cry for justice and land" during the Aty Guasu.

Guarani chief Getulio Potyvera sits inside the house of prayer on an ancestral land plot known as Tekoha Mykureati.

Guarani spiritual leaders perform the Mita Kara'i, a kind of baptism when children receive their native name and others have their spiritual protection renewed, during the Aty Guasu.

A Guarani Ava child lights a ceremonial pipe called a Petygua, used to ward off bad spirits, during a ritual as the group prepares to take back an ancestral plot called Tekoha Yvoh'y.

A Guarani Kaiowa woman stands watch near their makeshift camp on the edge of ancestral land known as Tekoha Takuara, where chief Marcos Veron was killed in 2003.

"Sandriely stuck two sooty fingers inside her mouth as she cried. “She’s hungry,” her grandmother said."

Three-year-old Sandriely has a look of suffering. She was born in a roadside camp along the same highway where her brother was run over by a truck. Her grandmother Damiana Cavanha, one of the few women chiefs among the Guarani Indians, has lost, beside her grandson, five other family members: one aunt died of poisoning from pesticides used on the neighbouring sugar cane plantation, and her husband and three of their children were hit and killed by passing vehicles.

Damiana, Sandriely, and 23 other Guarani Kaiowa Indians have been living in a makeshift camp along the shoulder of highway BR-463 in Mato Grosso do Sul since 2009. They settled here after their last failed attempt to take back their ancestral land, called Tekoha Apika’y. Tekohá is loosely translated as ancestral land, and Apika’y, the name of that specific plot, meaning “those who wait.” They were expelled from the land by gunmen, who shot one of them.

A federal prosecutor visited the camp back then, and wrote in a report, “Children, youths, adults and the elderly are subjected to degrading conditions against human dignity. The situation experienced by them is analogous to a refugee camp. They are like foreigners in their own country.”

Four years later, nothing has changed in Tekoha Apika’y. The Indians continue living squeezed between the road and a sugarcane field, which is part of the land they claim. Divided into eight huts, they do not have access to drinking water and depend on meagre donations of food.

Their children show obvious signs of malnutrition. They live with the constant danger of the trucks rumbling closely by them, loaded with Brazil’s rich agricultural commodities, some of which were harvested from plantations on the very land they are claiming as belonging to their ancestors.

I made two trips here, one in early August when Amnesty International’s Secretary General Salil Shetty visited. While I was photographing I heard him say, “I feel like I’m in a place where human rights don’t exist. This is really shameful for Brazil.”

Two weeks after that visit, a fire ravaged the camp, and I quickly returned. Three of the eight shacks were destroyed, and the Indians escaped just in time while their few belongings and food reserves burned. When I arrived I found the community desolate.

“The fire came to kill us, but we survived. Gunmen want to kill us, but we’re not leaving,” sighed Chief Damiana as soon as she recognised me. Her strength is amazing. Even after so many personal losses, she remains decided.

“The seed of my ancestors is in this earth and I will not give it back,” she said.

The cause of the fire remains unknown but Damiana told me how, the night after, gunmen invaded the shacks and threatened to kill the Indians if they didn’t abandon the site. The federal prosecutor opened an investigation into the threats and the possible connection with a major security company already accused of working as a private army for large landholders against other Indian communities.

I went in search of Sandriely, the girl born on the roadside, and found her crying, still frightened, amid the ashes. Her eyes, glistening with tears, contrasted with the grey destruction all around, and I couldn’t avoid thinking of my own daughter Ana, about the same age. Sandriely stuck two sooty fingers inside her mouth while crying. “She’s hungry,” her grandmother said.

BLOOD FOR LAND

“We’re taking back our land with our own blood,” said Getulio Potyvera, a Guarani Kaiowa chief who has received death threats. I met him in his home in the nearby city of Dourados at the beginning of August, as part of my first trip.

He invited me to into his ogapeysu’y, a thatch-roofed house of prayer. As he told it, there is a price on his head. His relatives told the public prosecutor’s office that they were confronted several times by men who were looking for Getulio, offering money for information on his whereabouts.

On the same trip I toured other Tekohas, including one near Caarapo where Indians are fighting to regain Tekoha Pindo Roky. Native women pay a daily tribute at the grave of Denilson Barbosa, shot dead at the young age of 15 by rancher Orlandino Carneiro, last February.

Carneiro confessed to the shooting and was arrested, but is now free on a plea of self-defence. Barbosa’s family is being kept under a government program to protect witnesses and victims of crimes.

The main victims in the land war are the Guarani, with a population of around 50,000 divided among the Kaiowa, Nandeva, and Ava sub-groups. Confined to small areas of land or camped on roadsides, these Indians suffer a long, bitter struggle to return to their traditional territories.

In the past year, Brazil has witnessed a more than twofold increase in violence against native peoples, according to a report by CIMI (Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples), linked to the Catholic Church. Just in Mato Grosso do Sul, 317 Indians were murdered in the past 10 years. The report also reveals that there were more than 200 attempted murders against Indians in the state during the same period, and, according to the Health Ministry, 470 Indians committed suicide.

Survival International calls the Guarani suicide rate an “epidemic”, quoting Guarani tribe members as blaming it on the loss of land and freedom, and nostalgia for their vanishing way of life.

Last October a group of 170 Guarani Kaiowas wrote an open letter that was interpreted by the media as a threat of collective suicide. In the letter they said they would die together before being evicted from the Tekoha that they were fighting to keep.