Remembering the killings

Damir Sagolj

Damir Sagolj

Some 2 million people are thought to have died under the rule of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge in the 1970s, one of the darkest and bloodiest chapters of the twentieth century.

Now, a U.N.-backed tribunal has sentenced the regime’s top two surviving cadres to life in jail for crimes against humanity.

Tourists stand behind a portrait of former Khmer Rouge leader Nuon Chea, also known as “Brother Number Two" in a former prison that has been turned into a Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh.

Both Chea, 88, and former President Khieu Samphan, 83, were found guilty of crimes against humanity orchestrated by the Khmer Rouge as part of its ultra-Maoist revolution from 1975-1979.

The two men face separate charges of genocide in a second phase of the complex trial. There were initially four defendants, but former Foreign Minister Ieng Sary died in 2012 and his wife and ex-minister Ieng Thirith has Alzheimer's disease and was ruled unfit for trial.

The latest ruling was only the second against "those most responsible" for the deaths of some two million Cambodians and could be the last handed down by a tribunal fraught with disputes and delays since its inception nine years ago.

Seventy-three-year-old Sok Teng, pictured above, was among the survivors and relatives of victims of the Khmer Rouge regime who came to hear the delivery of the verdict.

Most victims of the regime died of starvation, torture, exhaustion or disease in labour camps or were bludgeoned to death during mass executions at "killing fields" across the country.

Led by Pol Pot, the regime sought to turn Cambodia back to "year zero" in its quest for a peasant utopia. Pol Pot, or "Brother Number One", died in 1998.

Soum Rithy, who lost his father and three siblings under the Khmer Rouge, breaks down in tears and hugs another survivor after the verdict was delivered.

The United States embassy said it hoped the verdict would offer a measure of peace and justice for the "unimaginable hardship and misery" the Khmer Rouge caused.

The European Union said the ruling "demonstrates that any political leaders can be held accountable for their acts, even decades after".

A picture hangs on the wall in the Tuol Sleng prison, a school where as many as 14,000 people were tortured and executed, and which is now the Genocide Museum.

Kaing Guek Eav, who was head of the notorious former jail, was the first and until now the only person to be sentenced by the tribunal set up nine years ago to prosecute senior leaders of the regime.

It is unclear whether there will be enough momentum, or political will, to bring further trials. The court had spent more than $200 million by last year but has been plagued by delays, disputes, unpaid salaries and resignations, while donors' doubts about its efficacy have made funding difficult to secure.

The majority of Cambodians alive now were born after the bloody era and they embrace the capitalism the Khmer Rouge deplored. Their Cambodia has enjoyed unprecedented peace and development since the late 1990s, but judgment upon Pol Pot's henchmen is still significant for most people.

Memories of the killings still live on. “Rest in peace, never forgotten,” reads one message at Tuol Sleng prison.

Slideshow

Workers sweep the ground between former execution pits and mass graves where victims of the Khmer Rouge regime were killed.

A tourist sits on a bench at Choeung Ek, a "Killing Fields" site on the outskirts of Phnom Penh.

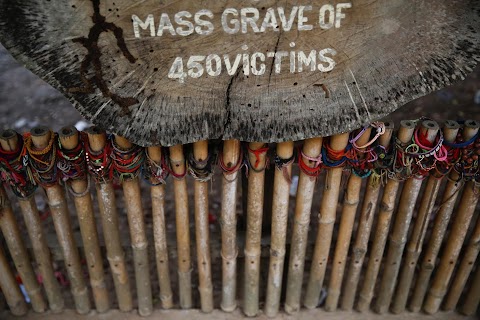

Colourful bracelets are left on a spirit house for victims of the Khmer Rouge regime.

Tourists visit the notorious former Tuol Sleng prison, which is now a Genocide Museum.

Chum May, one of the few survivors of Tuol Sleng prison, stands in the former cell where he was tortured.

A photograph hangs on the wall in a room once used as a torture chamber.

Torture instruments used by the Khmer Rouge are displayed at the former prison.

The skulls of victims of the Khmer Rouge regime are seen on display.

Skulls are stacked behind glass at a memorial stupa made with the bones of more than 8,000 victims at the “Killing Fields” site of Choeung Ek.

Tourists walk past hundreds of photographs of prisoners showcased in the former Tuol Sleng prison.

A visitor at the museum reads about former Khmer Rouge president Khieu Samphan.

Messages are left by visitors to Tuol Sleng.