Tough treatment

A man stands in tears, confined in a bamboo cell, towards the beginning of what will be a very difficult 40 days.

He is at the Youth for Christ Centre for heroin addicts in Myanmar’s Kachin state, a rudimentary drug rehabilitation facility where users are forced to go cold turkey and spend a week or so locked inside a cell as part of a 40-day course of prayer, Bible study and devotional singing.

Story

Faith Healing: Going Cold Turkey In Myanmar Behind Locked Doors

A year ago, Wun Naung Lay left his village in northern Myanmar to look for work and found heroin instead. Today, the skeletal 25-year-old is locked up and going cold turkey beneath a filthy blanket in a bamboo cell.

Wun Naung Lay is one of more than 600 young men who have undergone primitive drug rehabilitation at the Youth for Christ Centre, a collection of tin-roofed shacks on a riverbank in Kachin State.

Myanmar is the world's second-largest producer of opium after Afghanistan and use of its derivative, heroin, is widespread. The center's popularity is a testament both to the severity of Myanmar's drug problem and the lack of options for users in a poor country where modern treatment programs are rare.

It offers a 40-day "course" of prayer, Bible study and devotional singing, with football and weightlifting for those strong enough.

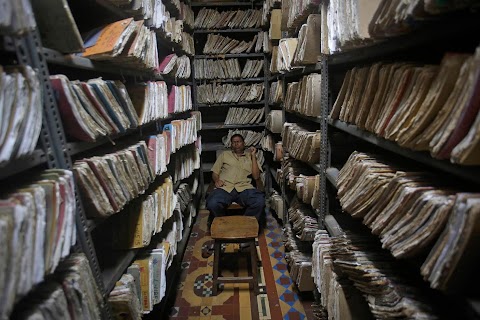

Detox begins in the Special Prayer Room, as the bamboo cell is called. New arrivals are locked in around the clock for seven to ten days.

"At first I just wanted to go home, but now I'm feeling a bit better," said Wun Naung Lay, whose forearms are perforated with needle holes.

The Youth for Christ Centre is the brainchild of Ndingi Laja, 45, a former convict and folk singer better known by his stage name Ahja.

A wiry and intense figure, Ahja believes his devotion to God helped him kick heroin while serving a nine-year sentence for drug use. Founded in 2009, a year after his release, the center is an attempt at faith-based abstinence on a larger scale.

His methods find little support among global health experts, who say voluntary drug treatment is not only more humane but also more effective.

They advocate harm-reduction policies, including needle-exchange programs and substitution drugs such as methadone, which focus on mitigating the ill-effects of drug use.

There is no methadone at Ahja's riverside rehab - he doesn't believe in it. "It isn't effective. You never escape the addiction completely," he says.

After their grim stint in the Special Prayer Room, the men are moved to a dormitory that is also locked at night. This discourages residents from sneaking out to buy alcohol or cigarettes, both banned at the center, or from running away entirely.

A quarter of the 65 males, mostly aged 15 to 25, who started the latest course have "escaped", said Ahja.

Some are farmers and laborers, others are students. They are usually Kachin, who are predominantly Christian, but some are from Buddhist ethnic groups.

Most arrive voluntarily, but some are brought by force with the help of staff members, many of them former addicts.

Ahja started his center with donations from fellow Christians. He charges each patient 40,000 kyat ($40), although poorer families pay less, sometimes nothing.

He insists his methods are effective, although he can't say how many patients stayed off drugs after leaving the center.

Around Myanmar, drug users are still criminalized and stigmatized. Under a law enacted when it was a British colony, even possessing a needle carries a six-month jail sentence.

A crackdown by police in Myitkyina, Kachin State, last year drove users underground and interrupted prevention and treatment programs that help combat the spread of HIV/AIDS.

About 20 percent of injecting drug users, most of whom live in heroin-saturated northern Myanmar, are infected, according to the Ministry of Health.